Let me outline just a few of the problems I've faced in trying to learn Mandarin:

1. Characters are totally non-phonetic

Chinese characters do not follow an alphabet, so you can't look at them and know how they sound like. The end result of this is it's possible that conversational Mandarin speakers have no idea how to read.

When I was getting set up here, Mo helped me purchase a wireless router at the electronics store. He adamantly tried to get me an English router, explaining to the store clerk that I could not speak Chinese. This led to a moment where the clerk asked Mo, "Well, can't you just read it for him?" Mo had to respond, "I am illiterate."

1. Characters are totally non-phonetic

Chinese characters do not follow an alphabet, so you can't look at them and know how they sound like. The end result of this is it's possible that conversational Mandarin speakers have no idea how to read.

When I was getting set up here, Mo helped me purchase a wireless router at the electronics store. He adamantly tried to get me an English router, explaining to the store clerk that I could not speak Chinese. This led to a moment where the clerk asked Mo, "Well, can't you just read it for him?" Mo had to respond, "I am illiterate."

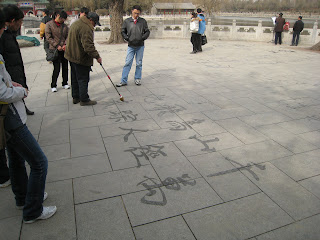

(Here's a picture I took of a man writing Chinese characters using a brush and water in Bei Hai park.)

Since Mandarin is non-phonetic, it has been romanized with a system called Pinyin. This means when someone says something like "mǎi," I can look up "ai" and realize that should sound like "eye" in English. But much of the romanized alphabet has no equivalent in English. I tried looking up how to say "jiān" for example (a component of asking "Where is the bathroom"), starting with the J.

J - No equivalent in English. Like q, but unaspirated.

So I looked up "Q"

Q - No equivalent in English...

3. Four tones for each syllable

Mandarin has four tones for each syllable, which changes the meaning of the word. There is a high flat tone, a rising tone, a falling-then-rising tone, and a falling tone. For example, the syllable "ma" is represented in Pinyin this way to get four words: Mā (mother), má (hemp), Mǎ (horse), Mà (scold). While in principle, I can tell the difference between these four sounds, remembering a word and its tone is super tough for me to do in real time.

Mandarin has four tones for each syllable, which changes the meaning of the word. There is a high flat tone, a rising tone, a falling-then-rising tone, and a falling tone. For example, the syllable "ma" is represented in Pinyin this way to get four words: Mā (mother), má (hemp), Mǎ (horse), Mà (scold). While in principle, I can tell the difference between these four sounds, remembering a word and its tone is super tough for me to do in real time.

As you might expect, it is possible to construct ridiculous sentences with this system. The below apparently means, "A little girl who is herding a cow finds it stubborn and so she pinches it," but only involves three syllables and multiple tones.

4. Looking (and indeed being) Chinese

There are 20 million people living in Beijing, and probably only a few hundred thousand foreigners. Of those foreigners, many are not Chinese. So no matter how you slice it, an Asian looking person who does not speak Mandarin is exceedingly rare in Beijing.

When I enter a restaurant, normally the waiters can quickly figure out that I don't speak much Mandarin. But I've learned how to say some simple things, like asking for ice water (Bīng shuǐ). Showing minimal competence tends to unleash a torrent of Mandarin, and waiters assault me with questions. The first time I asked for ice water, the fu wo yuen apparently asked me whether or not I wanted bottled water or not. I didn't know what she said, so I had to pass on getting water. I tried again at another restaurant, and the waiter asked me whether or not I wanted carbonated water, and if so, whether or not it should come in the big or small bottle. I didn't understand this at the time, but fortunately Mo was with me who could translate. Only on my third attempt was I able to successfully order water by myself.

In short, in my limited experience, I do think it's tougher to not speak Mandarin in Beijing when you look Asian.

("Let's Burger," which despite its name and clientèle, had waiters who spoke only Mandarin. The restaurant where I first successfully ordered ice water.)

1 comment:

My cousin recommended this blog and she was totally right keep up the fantastic work!

Post a Comment